How to stop your inbox from exhausting you

You know the feeling. It’s 10:27 AM, and you’re hunting for a critical client email from yesterday. You scroll past newsletters you don’t read, notifications about strangers, and a dozen promotions. Three minutes later, you find the email. It takes 45 seconds to read.

You just spent four times longer looking for work than actually doing it.

This is a fundamental design failure, and it’s costing you more than just lost time. We’re in a cognitive load crisis, and traditional email inboxes are the primary cause.

Your inbox vs. your brain: a mismatch by design

The core problem is that your inbox forces your brain to do sorting work that software should be doing for you. George Miller’s research proved that human working memory can only handle about seven items at once.

Yet your inbox presents dozens of different content types: urgent requests, newsletters, notifications, spam, all with identical visual importance.

Your CEO’s urgent message looks exactly like a Medium newsletter. You’re stuck burning mental fuel before you’ve even started working.

Compare this to how your brain processes a physical office, where important documents look different from break room magazines and enable instant categorization without conscious effort. Email interfaces ignore this natural cognitive advantage.

The real problem is interface overload, your brain is burning energy on poor design rather than meaningful work. This means that knowledge workers spend 2.5 hours daily in email, checking it every six minutes.

Most of that time is spent searching rather than communicating. That’s equivalent to losing an entire afternoon every day to interface problems.

Why the old “fixes” don’t work

- Folder systems create decision fatigue. You’ve traded the mental work of finding for the work of filing without reducing total effort.

- Gmail’s tabs are too rigid and often wrong. Important business emails land in “Promotions” while spam hits “Primary.” You end up checking all tabs anyway.

- Inbox Zero treats symptoms rather than causes, like organizing your junk drawer instead of questioning why you collect junk.

- Search only works if you remember what to look for.

These approaches make humans adapt to software limitations instead of making software adapt to how the brain works.

The real solution: visual hierarchy

Your brain processes visual weight before reading text. Important things should look important at first glance. This works because of “pre-attentive processing”—in milliseconds, before conscious attention kicks in, your brain can spot differences and group items based on visual cues.

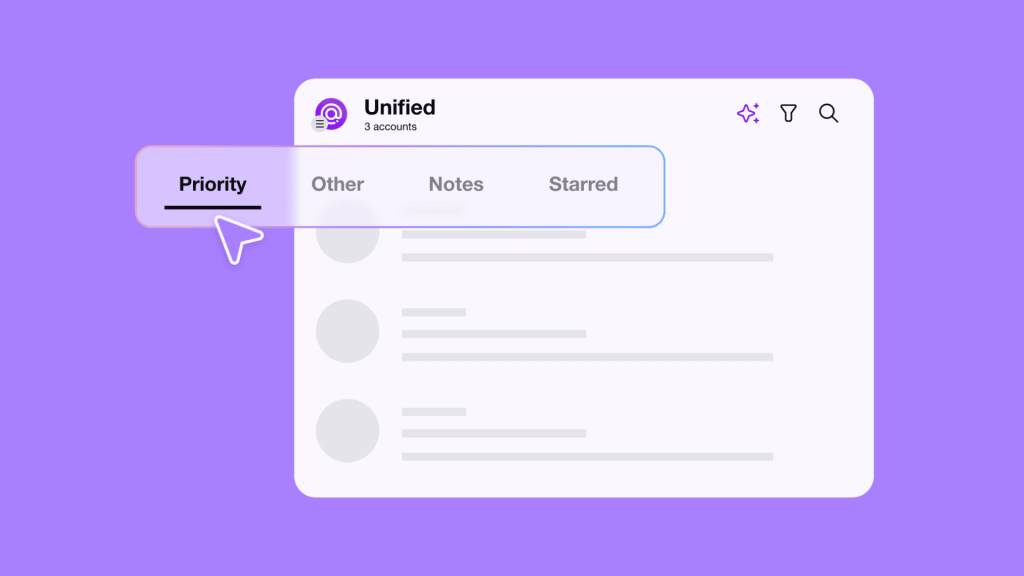

Work communications should be visually distinct from marketing emails because your brain processes them differently. This is how intelligent email design works:

- Priority Tab: Emails from colleagues and clients appear with visual importance that matches their actual importance to your work.

- Other Tab: Newsletters, promotions, and social notifications live separately, unable to interfere with mission-critical communication.

- Notes & Starred Tabs: Collaborative documents and marked items stay visually separate without manual folder management.

This lets your brain use fast, automatic processing for email instead of slow, deliberate categorization work. You’re freeing up mental energy for work that actually matters.

The bigger picture

Email dysfunction reflects broader software design failure: optimizing for technical constraints rather than human cognition. The cognitive load of poorly designed interfaces doesn’t just waste time, it creates decision fatigue that carries into your entire workday.

Fix your email interface, and you fix more than email. You reclaim mental energy being burned on software problems disguised as personal productivity challenges.

In five years, asking users to manually categorize emails will seem as outdated as asking them to defragment hard drives. The solution to inbox overwhelm isn’t better discipline, it’s smarter interfaces designed around cognitive science.

The technology exists. The design principles are established. The only question is whether email clients will evolve past the 1990s interface design.